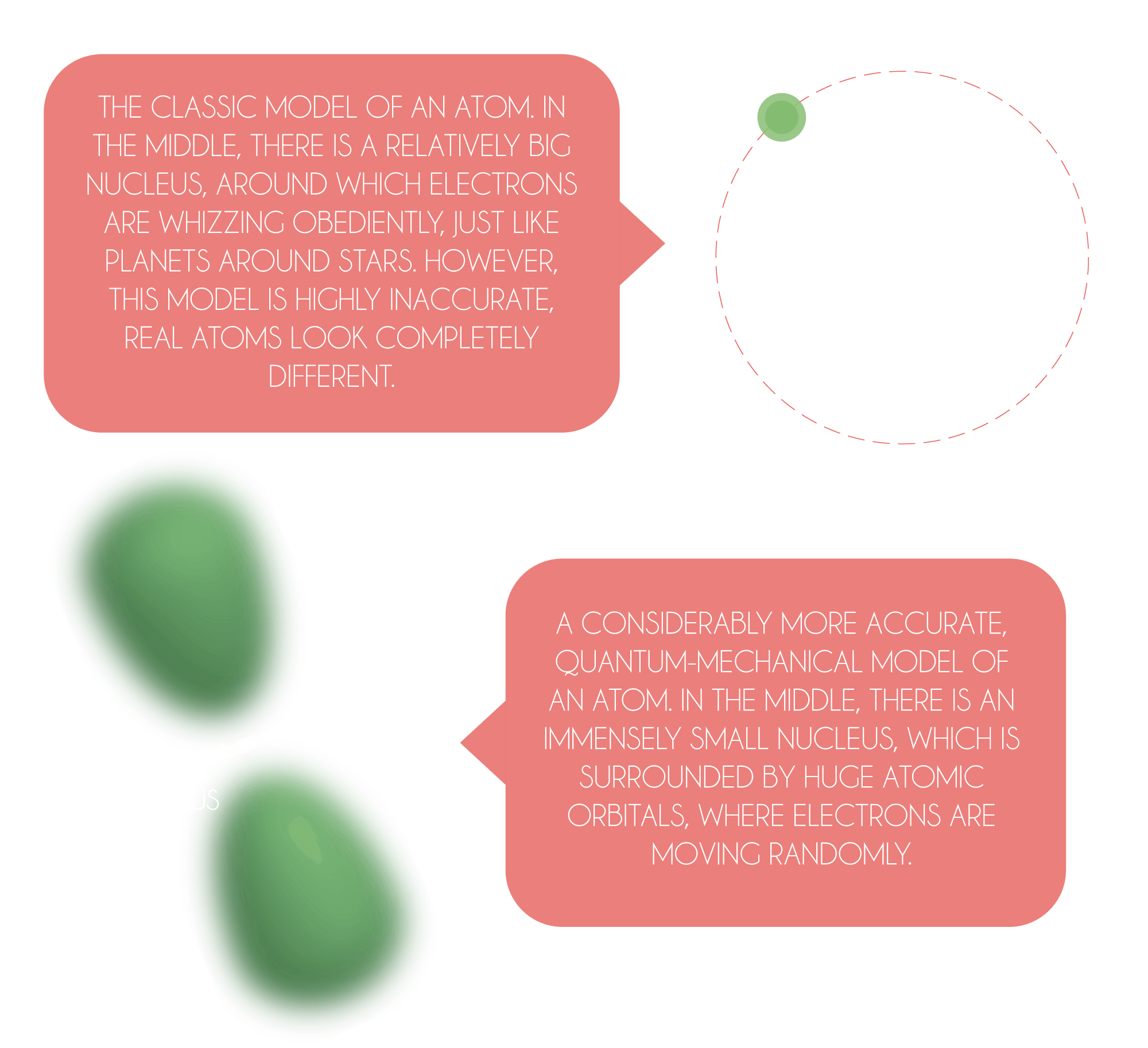

Every single object you see around you is made up of various atoms – tiny grains of matter. The human body, for instance, is composed predominantly from oxygen, carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen atoms. However, all atoms consist of even smaller grains – protons, neutrons and electrons. The number of protons inside an atom determines what kind of atom (or chemical element) we are dealing with. If you see an atom with only one proton in its core, it is surely hydrogen. If you encounter an atom with two protons, you are without any doubt dealing with a helium atom. Six protons? Carbon. Eight? Oxygen. We could go like this all the way to the number 92 – the number of protons in uranium, which is the heaviest natural element of the universe.

Your own atoms make up almost your entire mass. Every time you step on a scale, you measure the collective mass of all tangible subatomic particles that inhabit your body. But there is one important question – where do all of these particles come from?

To comprehend the sudden appearance of matter in the early cosmos, we first need to focus on the most famous physical equation on the planet, whose author is a world-renowned physicist Albert Einstein. E = mc2. Energy is equal to mass times the speed of light squared. Nice, you might say, but what exactly does it mean? Simply said, this brief equation daringly states that energy and mass are nearly the same thing. The only “converter” between the two quantities is the speed of light squared.

Take any object and multiply its mass by approximately 90 million billion – the value of the speed of light in meters per second squared. If you do that, you discover the immense amount of energy hidden inside the object. And you can do it in reverse too – if you take an arbitrary amount of energy and divide it by 90 million billion, you get its mass.

Exactly. Every form of energy weights something. A hot cup of tea is heavier than a cold one, as it contains more heat energy. However, you do not need to experiment and try to verify this fact by carefully weighing various tea cups at different temperatures – that is unless you live in a distant future where humanity is so technologically advanced that it can manufacture a hugely impressive scale which is able to detect differences of about a millionth of a millionth of a gram. Heat energy is far less concentrated than the energy we can find in matter. You would need to heat your cup to millions of degrees for a perceptible difference to appear.

The previous paragraphs could be summarised into one sentence – energy and matter are very closely related. So related, in fact, that you can create one out of the other. How? Well, if we consider the fact that each tiny bit of matter contains an enormous amount of concentrated energy, it would be logical to focus an unimaginable volume of energy to a single spot and hope that all of this energy would somehow “unite” and create a tangible particle. However, it is incredibly difficult to achieve that in today’s universe.

But if we consider how much condensed energy the early universe contained during the cosmic inflation (its temperature reached impressive billion billion degrees Celsius), we get stunning conditions for the creation of matter. The energy of the early cosmos was simply so concentrated that tangible particles started spontaneously forming.

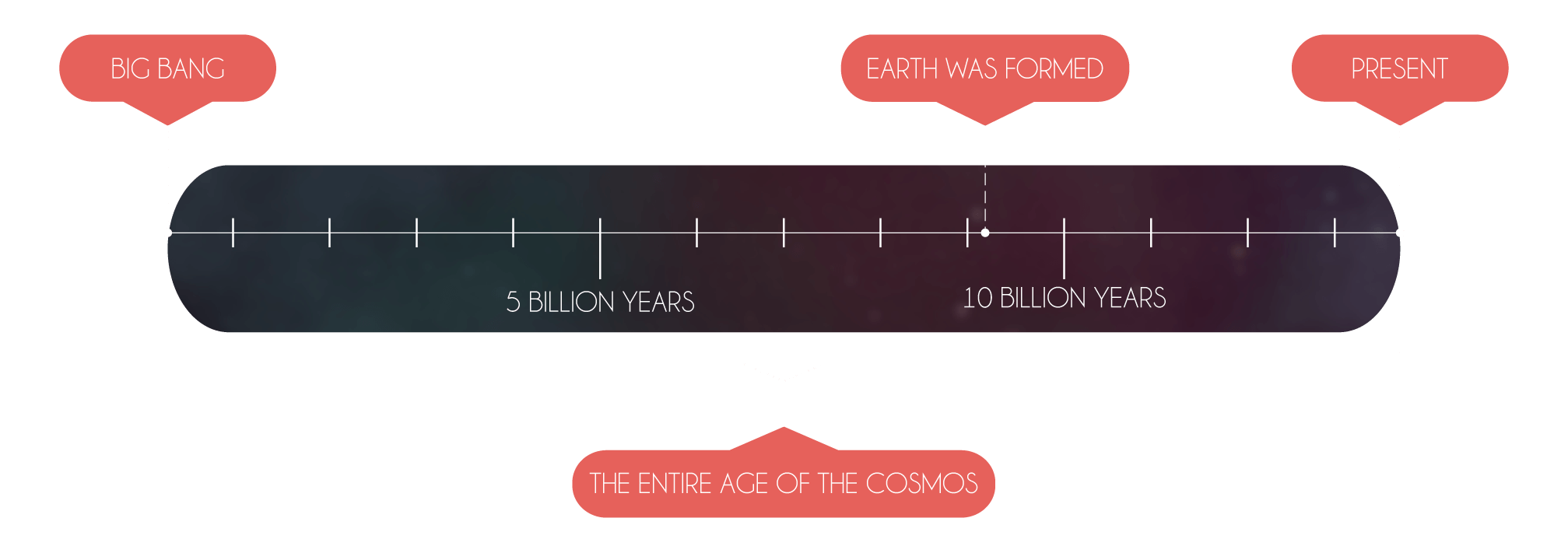

The formation of matter definitely did not take long though – all of it was created during the unbelievably quick cosmic inflation. At its end, the universe contained nearly all the matter you can see around you. Every single one of billions of stars and galaxies consists of the same matter that was created just a fraction of a second after the Big Bing, when the universe was about the size of a grape.

Back then, however, matter was far from forming atoms. For those, we have to wait several hundred thousand years. At that time, all matter was represented by the simplest of particles called quarks and leptons.

But there is a catch – the formation of matter is not that simple. There is a rule that with each particle of matter, its counterpart in the form of antimatter has to be created. Antimatter is just like normal matter, except that some of its properties are opposite – electric charge, colour or flavour. (The last two properties have obviously nothing to do with “our classical” flavour and colour – elementary particles cannot actually have any colour, since they are much smaller than the wavelength of visible light, not to mention flavour. They are just names physicists have given to various types of charges.)

But what is more interesting – matter and antimatter cannot stand each other. If they come into contact, both of them are destroyed in a violent explosion (this process is called annihilation) and all of their energy is transformed into photons – the particles of light.

Let us go back to the creation of matter in the early cosmos. It follows from the previous paragraphs that all the matter which was produced just a moment after the Big Bang had to be accompanied by the same amount of antimatter – each tangible particle was created along with its antiparticle. And since the universe was so incredibly small back then, the contact of particles and antiparticles was simply inevitable. Most of the newly created tangible particles crashed into an antiparticle and perished just a moment after their birth.

But there is one significant question. Why is there still matter in the universe today? By the laws of physics, the exact same amount of matter and antimatter should have been created. Theoretically, it follows that mutual destruction of all matter and antimatter should have occurred in the young universe. But that did not happen – otherwise we would not be here.

Nobody knows why, but it seems that for every several million antiparticles, one extra particle was created. Each of these surplus particles avoided annihilation and formed all matter we can see in today’s universe. It is staggering when we realize that the early universe not only contained nearly all matter it does today, it contained much more of it. And all of that was squeezed into a volume that would fit into a human palm.

However, the energy released in matter-antimatter collisions did not disappear. It was transformed into photons of high-frequency radiation. These photons then kept on roaming the newly created universe, which was packed with charged tangible particles. These particles prevented the photons from moving freely. It took 380 000 years before the universe became transparent due to the formation of atoms and photons were finally able to travel unimpeded. Many of these photons keep on cruising the universe to this very day and constitute the cosmic microwave background – living evidence of the Big Bang.