Gravity differs from the other interactions in multiple ways. First of all, it is by far the weakest of fundamental forces. In fact, we can simply demonstrate this fact. Try to lift an object using your hand. A pencil, a glass, anything. If you have succeeded and the object is safely in the air surrounded by your palm, congratulations – you have just managed to overcome the gravitational pull of the entire Earth, whose mass is in trillions of trillions of kilograms. How can gravity be the dominant force of the universe when it is so immensely weak?

The reason is that the other three interactions, though much stronger, simply are not customized to become the prevailing force of the universe. Strong and weak forces have a very short range – they only affect objects that are far less than a billionth of a meter apart. And the last interaction, electromagnetism, only influences objects with an electric charge. The problem is that you do not find such objects very often in the macroworld – most objects are neutrally charged. So the only reason that this ridiculously frail interaction has become the motive force of the cosmos is that it simply has no competition.

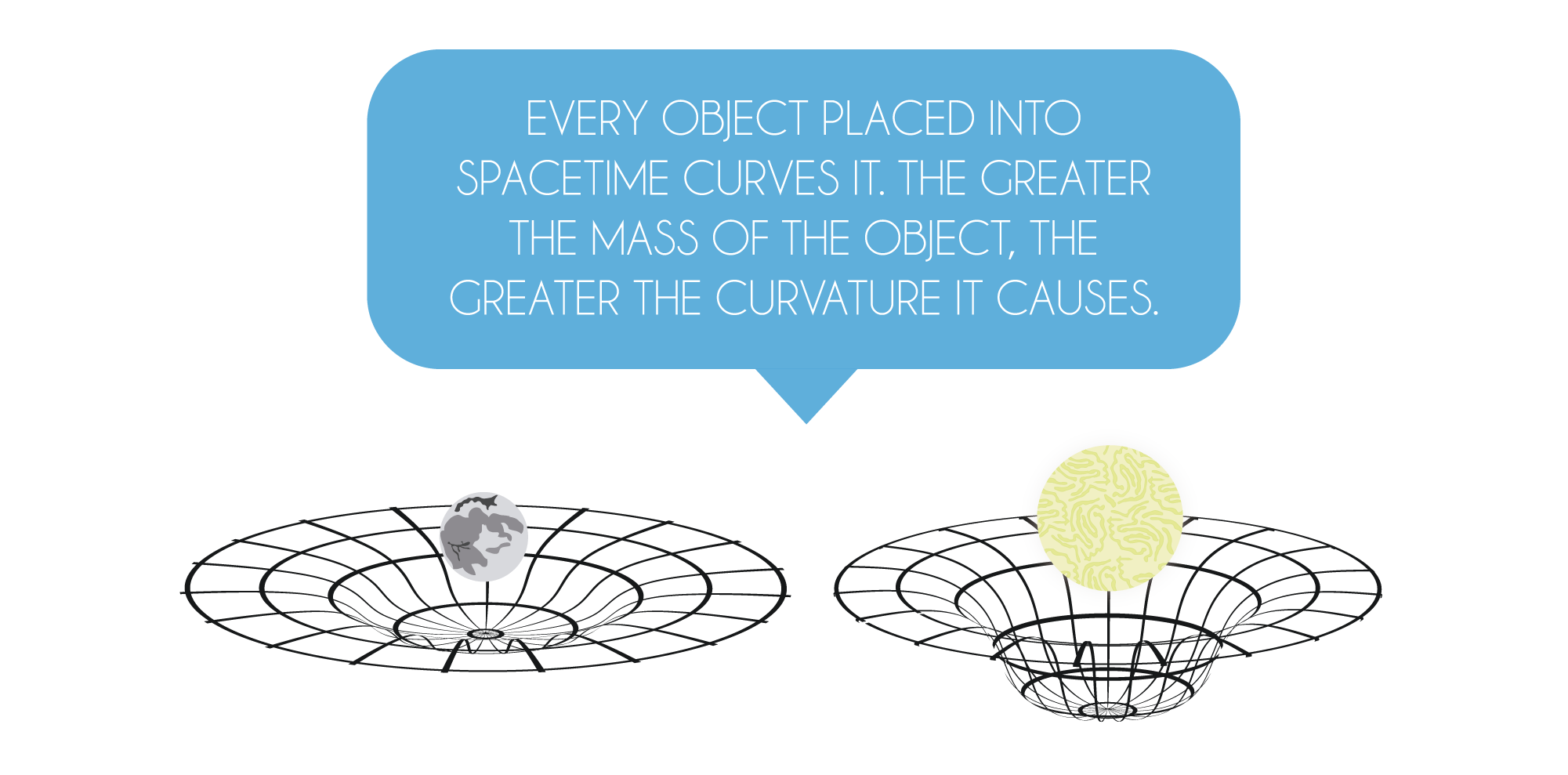

The second factor that makes gravity special is that it is presumably not really a force, even though it has been viewed as such to the beginning of the 20th century. However, with the advent of Einstein’s theory of relativity, our view of gravity has changed radically. Einstein saw gravity merely as a curvature of space-time. Every object in the universe simply creates a kind of dimple in the space-time continuum and all other objects are inclined to move closer to that object.

It is like placing a heavy object into the middle of a trampoline – the entire surface of the trampoline curves downwards, and if you place a different object near its rim, it starts to roll towards the original object. This analogy, however, has an imperfection. Just like with the inflation of the universe after the Big Bang, we need to take away one dimension to comprehend the phenomenon.

The surface of a trampoline can be perceived as two-dimensional space (it has width and height, but no depth) similarly to a sheet of paper. An object placed to its middle causes its two-dimensional space to curve. Therefore, the surface of a trampoline with an object in its centre can be understood as a two-dimensional space curved in the third dimension.

However, our universe is three-dimensional, so any curvature caused by the presence of an object in our space-time occurs in the fourth dimension. That is also the reason why we can never perceive any gravitational curvature. We would need to be four-dimensional beings for the curvature to be revealed to us.

However, it does not hurt to know that nobody is sure whether this theory of gravitational space-time curvature is true. With today’s technical advancement, we are struggling to find evidence that gravity indeed curves our three-dimensional space.

But there is another view of gravity, completely different from the one I have just described. According to this view, gravity is provided by a hypothetical particle called the graviton. How? Simply said, every two objects in the universe exchange various numbers of gravitons, which causes them to attract.

To understand why there are two different perceptions of gravity today, we first need to become acquainted with the greatest problem of today’s physics – the everlasting search for the theory of everything. To achieve that, we need to travel more than a hundred years to the past, to the beginning of the 20th century, where we will witness the birth of the two greatest physical theories of today.

By the end of the 19th century, some physicists presumed that physics was already complete. They thought that everything had already been described by the old physical theories. But then came the year 1900, along with a new revolutionary theory called quantum mechanics, which proved how immensely wrong those physicists were. This theory describes the behaviour of objects from the microworld, which is completely different form the behaviour of “normal” objects. Fifteen years later, classical physics was stabbed again by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which utterly transformed our view of gravity and beautifully described the motion of objects at high velocities.

However, there is a tremendous problem with these two theories – each one seems to describe a completely different world. While quantum mechanics successfully uncovers the peculiarities of the microworld, general relativity brilliantly describes the motion of objects of the macroworld. But if we wish to fully comprehend our mysterious universe, we need to unify these two incompatible theories into one. Physicists have been trying to achieve that for the past hundred years, so far without much success.

And the problem with today’s view of gravity rises from here. While the description of the remaining three interactions comes from quantum mechanics, the best understanding of gravity is provided by general relativity. Physicists therefore aim to describe gravity within the framework of quantum mechanics, so that it forms a single integrated theory. This non-existent theory is called the theory of quantum gravity or simply the theory of everything.

And that is the reason why there are two different views of gravity today – one almost perfect in the framework of general relativity, which is not compatible with other interactions, the other not so perfect within quantum mechanics, which is crucial for the upcoming theory of everything, but includes these peculiar particles called gravitons, which have never been detected.

Not to worry though – luckily, there are a few things that we know about gravity with certainty. Firstly, gravity is always attractive. There is no instance of two objects gravitationally repulsing each other. Secondly, gravity propagates with the speed of light, which is the highest velocity anything can reach when traveling through space-time. That means that if the Sun were to disappear now and stop influencing us gravitationally, it would take exactly 8 minutes and 20 seconds for us to notice it and free ourselves from the Sun’s gravitational field (at the same time, the Sun would also disappear from the sky, as the last of its light would reach our planet). Until then, the Earth would keep revolving around the non-existent Sun.

And the third fascinating thing we know about gravity is that its range is infinite. Your own body attracts all the other objects from the observable universe – though it may seem peculiar, you are gravitationally attracting your computer, every single person on this planet, or the Andromeda galaxy, located several million light years away. It goes without saying that the gravitational interaction between you and the objects around you is absolutely negligible – gravity is simply too weak and its power starts showing only with overwhelmingly huge objects.